Jacob Charnley

BA Philosophy and Religion

hiu8e5@bangor.ac.uk

hiu8e5@bangor.ac.uk

LGBT+ themes can be found in mythologies from many cultures around the world. These include stories centered around homosexual, bisexual and pansexual relationships, gender variance, transformation and identity. While many of the myths concerning these themes can be principally found in Greek and Roman mythology, they can also be unearthed in other European mythologies, as well as in Asian, African, Oceanic and the American ones. I will be exploring the myths concerning these themes in the context of the geographical area from which the cultures that developed them originated. I will be focusing mainly on myths where the themes of sexuality and gender are explicit over others which could be considered more interpretive or subjective. I will also be predominantly focusing on European mythologies, as they represent the biggest proportion of known myths containing evident LGBT+ themes.

Greek and Roman

Many of LGBT+ myths can be found in Greek and Roman mythology. For simplicity, this article refers to these gods by their Greek names. Homosexuality is a theme in many Greek myths; however, this is mostly between male Gods. It can be inferred from this that bisexuality was common in the Greek and Roman gods, particularly the males.

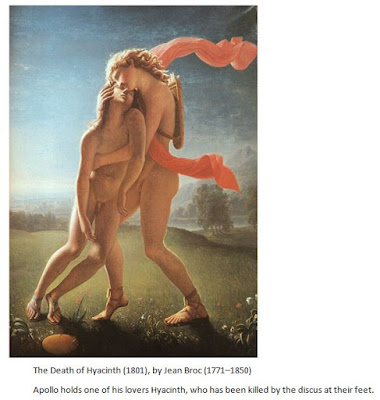

Apollo, god of the sun, knowledge and poetry to name a few traits, is associated with the greatest amount of homosexual relationships of any of the Greek and Roman gods. This would be appropriate for the patron of homosexual love. Perhaps the two most notable of his partners were Adonis, Aphrodite’s mortal lover (when he wasn’t Persephone’s), and Hyacinth, a Spartan prince. Other notable gods and figures with homosexual partners include Achilles, Dionysus, Heracles (Hercules to the Romans), Hermes, Poseidon and Zeus.

While Eros, god of lust, sex and eroticism, didn’t have any homosexual relationships himself, he was considered the patron of pederasty (a relationship between an adult male and an adolescent boy). Aphrodite as well is attributed patronage of lesbianism by the Greek poet Sappho (c. 630 – c. 570 BCE), while not having any recorded homosexual relationships herself.

Gender transformation is not uncommon in Greek myths. In some stories it is viewed as a reward, while in others as a punishment. An example of both can be found in stories relating to Artemis, goddess of hunting, and Leto, goddess of motherhood and mother of Apollo and Artemis. In the case of Artemis, she decided to transform the hunter Sypretes of Crete into a woman, after she caught him staring at her while she was bathing. Leto meanwhile sees the plight of a young woman named Leucippus, whose father Lamprus told her mother, Galatea, that he would refuse to acknowledge their child unless she had a son. Galatea gave birth to a daughter and decided to give her a male name and raise her as a boy, without her husband’s knowledge. As Leucippus grew older, it was becoming harder to maintain her disguise. Galatea prayed to Leto to bestow the same transformational magic Artemis used on Sypretes on her daughter. Leto took pity on her and granted Leucippus manhood.

Androgynous and intersex themes can also be attributed to the Greek myths. Hermaphroditus (from which the term ‘hermaphrodite’ originates), is the god of hermaphrodites and intersex people. Referred to as the son of Hermes and Aphrodite, he is usually depicted with a mainly feminine body, including both breasts and male genitals. Hermaphroditus’s story is also one of transformation, as he was originally born male, but when the nymph Salmacis was overcome with lust for him and raped him, she pleaded to the gods for them to never be parted. Her wish was granted, and Hermaphroditus in his new form asked that the pool in which the transformation took place bestow the same for anyone who entered.

Dionysus was attributed the patronage of hermaphrodites and intersex people by Roberto C. Ferrari in the Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture (2002). While Dionysus himself was not a hermaphrodite or intersex, Ferrari attributes this patronage to him due to his birth from both his mother Semele and father Zeus, his effeminate nature and his choice of wearing women’s robes.

Apollo and his twin sister Artemis are depicted as having characteristics of the opposite sex. Apollo is described as ‘eternally’ beardless and effeminate, while Artemis is considered more masculine. Apollo and Artemis can be seen in ancient Greek art engaging in roles more commonly performed by the opposite sex e.g. on the Lucanian Red-Figure Volute Krater, a mixing vessel which can be found in the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Norse and Germanic

Norse mythology contains a handful of notable stories with themes relating to homosexuality, transformation and gender roles. However, it should be noted that the tone of some of these stories are mocking, particularly to homosexual males considered less ‘manly’.

This is conveyed in the Gudmundar Saga – according to David F. Greenberg in his book, The Construction of Homosexuality (1988) - where a disloyal priest and his mistress are punished by having a group of men rape them both. Another example is that of Sinfjötli, half-brother of the legendary hero Sigurd, boasting that the einherjar (warriors who had died honourably in battle, receiving an afterlife in either Odin’s or Freyja’s halls) all fought each other for the love of Gudmundr, a king of the mythological realm of Jötunheimr, the realm of giants. On another occasion it was claimed that Gudmundr would give birth to nine wolf cubs, of which he was the father. To be the ‘receiving’ partner in a homosexual relationship was stigmatised, but not the more ‘manly’ and dominant role, which was coveted my many of these characters. Odin, All-Father and chief deity of the Norse gods, would have also faced stigma for his pursuit of magic, which was in the sagas considered an effeminate practice.

It is important to also reference that Freyr, god of fertility, is attributed with having a group of homosexual and effeminate male worshippers in Saxo Grammaticus’s Gesta Danorum. Loki, the god of tricks and mischief, is said to have transformed himself into a mare and mated with the stallion Svadilfari, giving birth to his foal, Odin’s eight-legged horse Sleipnir.

It is important to also reference that Freyr, god of fertility, is attributed with having a group of homosexual and effeminate male worshippers in Saxo Grammaticus’s Gesta Danorum. Loki, the god of tricks and mischief, is said to have transformed himself into a mare and mated with the stallion Svadilfari, giving birth to his foal, Odin’s eight-legged horse Sleipnir.

Gender non-conforming behaviour can be found in the poem Thrymskvida, where the giant Thrymr steals Thor’s hammer, Mjolnir, demanding Freyja, goddess of love and beauty, to marry him as payment for its return. Rather than send Freyja to him, Thor and Loki travel to Jötunheimr, with Thor disguised as the ‘bride to be’ and Loki as his bridesmaid. Thrym hands Mjolnir to Thor as part of the ceremony, which Thor utilises to defeat all the giants present.

Celtic

Celtic mythology is sparse in its reference to LGBT+ themes. This is most likely due to the record of many myths being lost post-Christianisation rather than none existing in the first place.

One notable story can be found in the Mabinogion. Two of the sons of the King of Gwynedd, Math fab Mathonwy, Gwydion, the magician, and Gilfaethwy, a demi-god, devise a plan to rape Math’s servant, Goewin. Goewin was important to Math as she was a virgin, and it is claimed that Math had to rest his feet in the lap of a virgin, or, unless he was at war, he would die. Gwydion offers to travel to the kingdom of Dyfed, to the south, to acquire otherworldly pigs. He offers Pryderi, King of Dyfed, horses and dogs in return for some of his pigs. However, he had conjured these animals, and when Pryderi discovers he has been deceived, he declares war on Gwynedd, and Math leaves to fight in defence of Gwynedd. While he is away, Gwydion and Gilfaethwy rape his servant Goewin. When Math returns to rest his feet in her lap, he realises she is no longer a virgin. He discovers Gwydion and Gilfaethwy are responsible for the recent events and curses them to turn into a deer, a boar and a wolf, each form for a year at a time, with Gwydion remaining male, but Gilfaethwy becoming female. They are then forced to mate every year, producing a son each year, after which their curses are lifted.

Conclusion

To conclude, there is so much more to be said on the portrayal of LGBT+ characteristics in European mythology alone. Two things stand out more than anything else. Firstly, how far back in history these discussions about sexuality and gender, positive or negative, reach. Secondly, how these stories have lived on and resonated, not only with the people and artists that shared and believed in them, but hopefully with you as well.

It is a comforting thought to think that the struggles we face today around these issues are far from new and neither are they isolated to particular cultures. Perhaps that reflecting on what has come before will make our journeys to who we are meant to be more assuring. These stories reveal, at least in part, that religious belief (or lack thereof), sexuality and gender identity are far more than just compatible, they are interconnected in ways that show us humanity is not all that different now to what it was in the distant past.

No comments:

Post a Comment